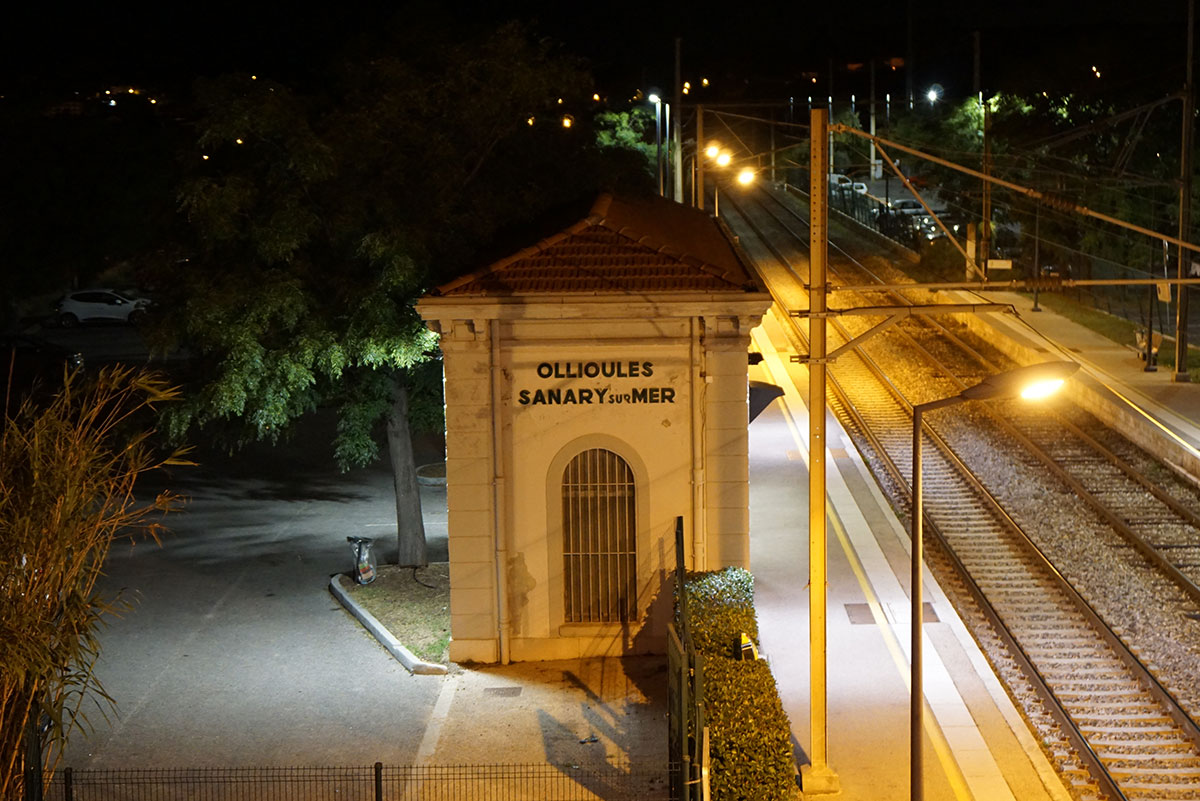

A journey at the end of September, which I make despite Corona concerns: I arrive by train from Marseille around midnight. The station, built for the towns of Ollioules and Sanary-sur-Mer together, is deserted but brightly lit – which puts me in the mood for the theme of the lights.

On the temple-like façade, which heralds the grandeur of the small towns on the Côte d’Azur, the names are written in large letters. So I have it in black and white that I am in the right place. The place where many German-speaking emigrants met in the 1930s, including the Manns.

In the monograph on the Mann family by Hans Wißkirchen, published by Rowohlt, I had found a photograph showing the town’s harbour at the time when the emigrants were staying there. In the background the ridges along the coast – and prominently in the foreground in the middle, like a standard, a lamp. It was not least this picture that gave me the idea to insert a lamp from Sanary into the monument in Munich.

This luminaire is still there today, in 2020, and the paving with the limestone slabs seems to be the same. It has three spheres of real glass, as I was shown on site, is painted sea green and bears the coat of arms of Sanary, a tower at the harbour, on its mast.

In Sanary, the memory of the emigrants from Germany and Austria is firmly anchored: Right at the harbour there is a large commemorative plaque which Sanary calls a „Lieu de Mémorie Vivante“, thus emphasising liveliness and relevance to the present. Trilingual, also in German („Gedenkort“) and English („Memorial site“), the plaque addresses an international audience, as international as the emigrants and the visitors who follow their traces. It lists some 70 names, a who’s who of German literature at the time: Ernst Bloch, Bertolt Brecht, Lion Feuchtwanger, Alfred Kerr, Ludwig Marcuse, Erich-Maria Remarque, Joseph Roth, Franz Werfel, Arnold and Stefan Zweig … The name „Mann“ is represented in large numbers, six times, with Heinrich, Thomas, Katia, Erika, Klaus and Golo.

But the commemoration is also linked to places of interest, leisure activities, tourism: the plaque is located outside the pavilion of the Office du Tourisme. To the left of it, screens show films about diving, sailing and the zoo. On the right, a smaller board tells the story of the emigrants who came to Sanary in the 1930s. Thomas Mann acts as their representative. The respective places of residence are marked with similar boards. The result is a parcours of the places and the memory of their former inhabitants.

I walk up the hill from the harbour. Pass a chapel with votive tablets, on the left side with a view to the sea. At the end of the road I come across the house that Thomas Mann lived in, the Villa La Tranquille. Here the houses have been given names, personalising them, names that evoke harmony and natural beauty. When I am there, however, it is anything but quiet: an angle grinder screeches nearby. The present once again speaks out. Nevertheless, I can understand the peace and seclusion of this small coastal town and begin to understand why the men and other emigrants came here.

For Thomas Mann, the house looks almost modest compared to his Munich villa, the one in Princeton or even the one in Pacific Palisades. But Katia and Thomas Mann did not live here for long either, for about nine months in 1933; it was a place of transition before they moved to Küssnacht on Lake Zurich, then later to America.

The next day there will be a meeting with representatives of the city to discuss questions about the monument project and the luminaire from Sanary. Patricia Aubert, Deputy Mayor, Jean-Pierre Moularde, Head of the Department of Technology, and Amandine Alivon from the Municipal Archives will be present, as the project is also about the history of the town. The municipality is willing to contribute a light for the monument. With the help of the company, which still has moulds, this will be possible. The parts still have to be collected and restored. And it is also a matter of mediation: whether, for example, references to the monument can also be attached to Thomas Mann’s former house. I am asked an interesting question: what is my artistic contribution, my modification of the lamps? I answer with Duchamp that the selection in itself is an artistic act, that it is about creating references. For my rather passive knowledge of French, the meeting is a challenge.

I treat myself to a room in the Hotel de la Tour, an angular-cubic building, built around the tower that is the symbol of Sanary, as it appears on the coats of arms on the lamp-posts. It was also the hotel where Klaus and Erika stayed during their stays. The fact that it was designed for permanent guests, who also received their mail here, is shown by the shelf with compartments on which the room key is hung when leaving.

From the window and from the tower there is a view of the sea, ships and lighthouses. Further back, you can see wooded and rocky ridges rising to the north and east. They exert a strong attraction on me, and after the meeting in Sanary, I explore the area from nearby Toulon for a few days and walk back towards Marseille. On the way I get into heavy rain showers on a mountain ridge and a storm that almost blows me down. So the weather and the landscape are not always as Mediterranean as the name of Thomas Mann’s villa „La Tranquille“ promises (who wisely left the area again in September).

By the way, there is a rich literature about Sanary, such as Das flüchtige Paradies. Künstler an der Côte d’Azur [The Fleeting Paradise. Artist on the Côte d’Azur] by Manfred Flügge (2008). A good review and summary here. Or Exil unter Palmen. Deutsche Emigranten in Sanary-sur-Mer [Exile under Palm Trees. German emigrants in Sanary-sur-Mer] (2018) by Magali Nieradka-Steiner.